|

| |

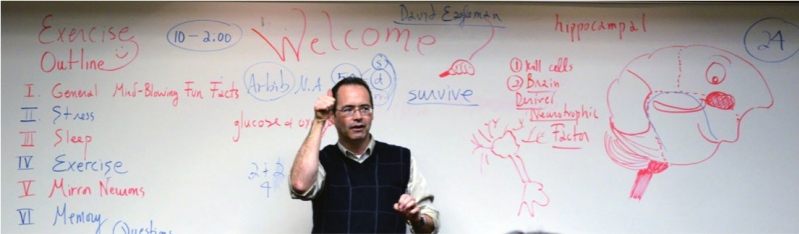

I Feel, Therefore I am: Exercising the Emotional BrainPatrick T. Randolph, Western Michigan University This article is the third in a multi-article series based on “What Every Teacher Needs to Know About the Brain,” a presentation given at the 2013 ITBE Convention in Lisle, IL.

Introduction “I am not an ‘intellectual.’ If anything, I’m an ‘emotional.’ I think most people are. Descartes should have said, ‘I FEEL, therefore I AM.’” —Vernon E. Johnson Emotions are the core elements that make us human; they are the musical notes of the mind, the songs of the soul; they are what make each of us unique and creative beings. There is no denying this simple fact. And, as it turns out, emotions also help our brains in the learning process and affect how we learn (Damasio, 1994; Jensen, 2008; Le Doux, 1996; Medina, 2009; Ratey, 2002). Without emotions, the brain doesn’t learn much. This concept dates back to Plato who advocated for the educational duet of emotion and learning in The Republic: “… the mind will not retain anything that it is forced to learn … we must not keep the children at their studies by force. Instead we must make learning fun” (Trans. 1985, p. 230). The idea of enjoyment and learning is reinforced by neuroscience—students learn when they are happy, when they are motivated, when they yearn to make themselves mentally stronger (Jensen, 2008; Medina, 2009). And, after all, the noble subject of philosophy itself is not defined as a “rational acquisition of knowledge,” but rather a “love of wisdom.” It is that emotional link, that passion to learn, which nurtures the pursuit of wisdom and personal development. The Importance of Emotions in Learning “We are driven by our emotions.” —Eric Jensen Can we truly learn anything that is not tied to us emotionally? Take, for example, an elementary school student who needs to learn a list of vocabulary items for a quiz. One could argue that there is no real emotional content in this. He either learns it or not. However, even this task has a connection to the emotions—he either learns it because he “wants” to, or he learns it out of the “fear” of failure. There is really no escape from our emotions and their influence on how and what we learn, for they “are an integral aspect of the neural operating system” (Jensen, 2008, p. 83). Chemically speaking, let us return to the wonderful world of neurotransmitters that we discussed in the previous article on the brain and physical exercise. We learned that exercise helps elicit numerous productive neurotransmitters for learning like serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine and norepinephrine. Emotions do the very same thing—that is, they help release certain neurotransmitters that aid in the learning process. For example, when the brain gets excited over something, let’s say learning an intriguing new idiom like “walk on air” or “feel like a million dollars,” the amygdala—a crucial area for processing emotions—releases the neurotransmitter dopamine into the neural system. This is significant to the learning process because a neuro-chemical like dopamine, as you may recall, helps considerably in the formation of memory and in the processing of valuable information (Medina, 2009; Ratey, 2002). Furthermore, ideas and experiences that are tied to strong emotional content will last “much longer in our memories and are recalled with greater accuracy than neutral memories” (Medina, 2009, p. 80). That is to say, emotions aid in encoding information and help retrieve it with ease. Think back to a fond memory from childhood that has a strong emotional content. Chances are, you recall it as clear as day this very moment. So, information, be it in or out of class, learned with an emotional tie will have a better chance of being sent to the long-term memory. In sum, emotions help students both learn new material and remember it longer, if not forever. In a recent survey I conducted in three classes, I asked a total of 42 students which of the basic emotions (joy, sadness, fear, surprise, anger, and disgust) best help them learn new material in their ELL classes. Fear won out with 21 votes followed by joy and surprise both with 20 votes. Sadness received 3 votes and anger 4. Disgust only managed to attract one vote. Every student cheerfully participated in the survey, and every student said that without some kind of emotion involved with their studies, they have a hard time not only learning the information or skill but also just getting involved with it. Although the above is but a small sampling, it clearly shows how influential emotions are in the classroom. As we truly are “driven by our emotions” (Jensen, 2008, p. 88), we must make a concerted effort to incorporate them in our daily lessons. Facilitating Emotions in the Classroom “One is certain of nothing but the truth of one’s own emotions.” —E.M. Forster All too often when we teach, we focus only on getting the students to acquire the material for tests, assessments, and, even more sadly, for favorable teacher evaluations. What we should be focusing on, however, is motivating our students’ emotions, hearts, and adding fuel to their passion for learning. How, then, can we help facilitate more emotion in the ELL classroom? The following is what I call the five Es of emotional learning: 1) educating through personal involvement, 2) examples, 3) energy, 4) exercise, and 5) euphoria. 1) Educating through personal involvement: This first “E” is based on Eric Jensen’s idea of role modeling in the classroom (2008). If you are teaching a writing class, then join the students and write with them, or talk about a writing project that you might be working on like an article submission or a conference proposal. The point is to get involved with their learning by showing that you too are learning or doing what they are doing. Show by doing! 2) Examples: When teaching vocabulary, have your students give examples of the terms. This simple activity will help them gain ownership of the material. There is a strong possibility that the students will personalize these examples, which will help evoke even more emotion and personal interest in the vocabulary (Randolph, 2013). Moreover, inspiring your students to give examples pushes them to become cheerful risk-takers—a very necessary element for language learning success. 3) Energy: As Medina tells us, “We don’t pay attention to boring things” (2009, p. 71). In order, then, to elicit arousal in the classroom, the instructor’s energy and excitement should be at an emotion-provoking level. How that is determined depends on the instructor, but it should be at a degree which commands attention. That is, instructors need to be aware of the volume and clarity of their voice, their effective use of gestures, and their use of eye contact and eyebrow movement. Every detail of physical language adds to the needed energy for students to get emotionally involved in the learning process. 4) Exercise: The second article in this series discussed, in great detail, the literally vital importance of physical exercise in the classroom. As mentioned, instructors should get their students up and moving every 20 minutes or so (Jensen, 2008). This helps pull in oxygen to the brain and activates those necessary neurotransmitters that affect emotion, memory, and learning in the ELL classroom. 5) Euphoria: In the first article in this series, I examined the importance of mirror neurons. We can now revisit the significance of these neural creatures regarding the importance of creating a cheerfully “euphoric” classroom atmosphere. If the instructor is happy, his or her students will “mirror” that and become happy, motivated students themselves. Furthermore, euphoria and humor nurture a sense of feeling “at home,” they relieve stress and help the students reach within to access the emotions that motivate them to learn and feel the need for self-improvement. Concluding Remarks “If you laugh, you think and you cry, that’s a full day.” —Jimmy Valvano Can we measure success by increasing the use of emotions in the ELL classroom? The skeptic will respond in the negative and argue for a stoic-based environment in which only reason and critical thinking are allowed. I, however, think that we can all agree, as Plato claimed, that making learning “fun” is really the only way to inspire the students to become passionate about their own education. Moreover, I think we can also agree that when the instructor is having an enjoyable time, the students get excited as well. The brain is not just a thinking organ; it is also a very emotional one. How we learn does depend on how engaged we are, and emotions, perhaps more than anything, are a sure way to spark, maintain, and expand the ELLs’ interest in and love of learning. Correspondence concerning this article can be addressed to patricktrandolph@yahoo.com. Patrick T. Randolph currently teaches at Western Michigan University where he specializes in creative and academic writing, speech and debate. References Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. New York: Putnam and Sons. Jensen, E. (2008). Brain-based learning: The new paradigm of teaching. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. LeDoux, J. (1996). The emotional brain. New York: Simon & Schuster. Medina, J. (2009). Brain rules. Seattle, WA: Pear Press. Plato. (trans. 1985). The Republic. R. W. Sterling & W. C. Scott (Trans). New York: NY: W. W. Norton & Company. Randolph, P. T. (2013). What’s in a name? Personalizing vocabulary for ESL Learners. CATESOL NEWS, 44, 12-13. Ratey, J. J. (2002). A user’s guide to the brain. New York: Vintage Books. *Photo credit: Kelly Cunningham | |

| ITBE Link - Fall 2013 - Volume 41 Number 3 |