|

| |

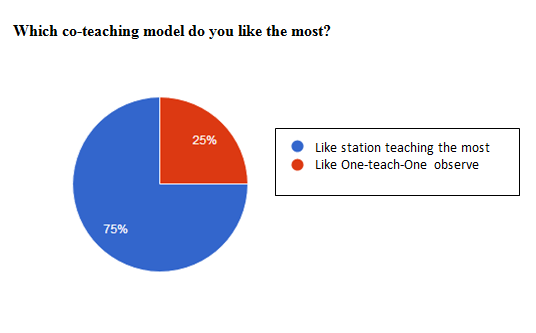

The Impact of Co-Teaching on Meeting the Needs of English Language LearnersBy Asma QaziAccording to a report from the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition (2011), 51% more ELLs have enrolled in grades from prekindergarten through 12th grade (PK–12) in U.S. public schools between the years 1998–99 and 2008–09 (August, Estrada, & Boyle, 2012). With a continuous increase in ELL population, creating an academically challenging environment for all the students, including ELLs, has become a key component for the teachers while planning and implementing lessons in such diverse group of classrooms (Imbeau & Tomlinson, 2010). One of the goals for educators is to see that we are meeting the needs of our students based on each student’s learning styles and interests. Therefore, my research question during my Master’s program in Curriculum and Instruction was: How effective is co-teaching in meeting the needs of English Language Learners? The purpose of my action research was to inquire about the effectiveness of co-teaching on the performance of English Language Learners. The data collected revealed that although co-teaching can be very engaging and fun for ELLs and offers them a welcoming learning experience, teachers need time to efficiently plan and should have a common understanding. Co-teaching provides teachers with a greater opportunity to learn about the different cultures of their students that are a diverse mix of ELL and non-ELL students while enthusiastically experimenting with new instructional methods and content-related strategies. Moreover, co-teaching offers co-teachers opportunities for differentiated instruction for ELLs and students with special needs, and their collaborative work directly leads to a successful co-taught classroom and results in clearer directions and descriptions for teaching. In addition to this, co-teaching also increases the quality of student learning (Vaughn et al., 1997; Pappamihiel, 2012; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 2017). Co-teaching eases progress monitoring, helps reach ESL students without being pulled out from their mainstream classrooms (Vaugh et al. 1997; McClure and Cahnmann-Taylor, 2010; Pappamihiel, 2012), and effectively addresses behavioral problems that may arise in a co-taught classroom. Pappamihiel (2012) observed that co-teaching models help ELL teachers to offer accommodations in a mainstream class itself without students being pulled-out. Also, it will be easier for ELL teachers to progress monitor any ELL students that might have been exited based on their ACCESS score. This would help make a smooth transition for ELL students since the ELL teacher is still in the same classroom helping other ELLs who have not exited. In fact, he also stated that the teachers whom he interviewed noted that both ELL and non-ELL populations in the co-taught classrooms benefited from the accommodations. Mastropieri (2017) also mentions that if co-teachers are provided with opportunities for professional development, it will expose them to pedagogical skills needed to effectively plan and promote learning for all the students in a co-taught classroom. Mandel and Eiserman (2015) stated that co-teachers constantly learn from each other during the co-teaching process, which in turn leads to each other’s professional development while teaching. Co-teachers can also share their ideas, give feedback to each other, and offer suggestions. There are two main models of co-teaching: station teaching and one-teach-one-observe. When interviewed, 75% of teachers liked the station teaching model the most, and 25% of teachers liked one-teach-one-observe co-teaching model (as observed in the figure below).  In an interview, co-teachers stated that they have effectively used multi-level questions, highlighted materials, learning logs, role plays, Web quests, manipulatives, and rubrics matching varied skill levels. On the other hand, during Transitional Bilingual Education time with an ELL resource teacher, students were grouped according to their ACCESS scores, whether in a co-teaching model or a pull-out group. It has also been observed that ELLs felt good in a pull-out group as they also got to do different activities here, which were sometimes different from what the rest of their classmates were doing in their classroom. Based on my data collected, it has been noted that with efficient and deliberate co-planning, teachers can make the lessons even more motivational. Inclusion of technology and using the station co-teaching model seems to improve student-student interaction and boost their intrinsic motivation. Additionally, grouping students based on their ACCESS scores and also heterogeneous grouping helps ELLs perform better in their mainstream classroom. On the other hand, the results from their MAP reading scores showed that students performed equally well on this standardized test, irrespective of co-teaching. This study could be improved by comparing students’ MAP scores with their ACCESS scores and by including the entire class’s formative and summative assessments. Additionally, narrowing the data collection may offer a more succinct study. References August, D., Boyle, A., & Estrada, J. (2012). Supporting English Language Learners: A pocket guide for state and district leaders [Pamphlet]. Washington D C: American Institutes for Research. Imbeau, M. B., Tomlinson, C., & ASCD. (2010). Leading and Managing a Differentiated Classroom. ASCD. Mandel, K., & Eiserman, T. (2015). Team teaching in high school. Educational Leadership, 73(4), 74. McClure, G., & Cahnmann-Taylor, M. (2010). Pushing back against Push-In: ESOL teacher resistance and the complexities of coteaching. TESOL Journal, 1(1), 101-129. Pappamihiel, N.E. (2012). Benefits and challenges of co-teaching English Learners in one elementary school in transition. The Tapestry Journal, 4 (1), 1-13. Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (2017). Making Inclusion Work With Co-Teaching. Teaching Exceptional Children, 49(4), 284-293. Vaughn, Sharon, et al. “The ABCDEs of Co-Teaching.” TEACHING Exceptional Children, vol. 30, no. 2, 1997, pp. 4–10., doi:10.1177/004005999703000201. Asma Qazi is an ELL Resource Teacher in School District 45. | |

| ITBE Link - Fall 2018 - Fall 2018 |