|

| |

Disciplinary Literacy: Empowering Teachers and Students with Tools to Access Complex Academic LanguageBy Sara Vroom Fick As language teachers, we are used to exploring language, looking for patterns, nuances, and applications. Students of language are used to that as well, searching for those high profile patterns that will help them understand chunks of language. However, in language development classes, our focus is often on broad uses, and we can fail to take into account variations for specific contexts and purposes. This can lead to students applying learned patterns across all contexts, inevitably creating errors in usage or less than ideal communication. Additionally, content-area teachers who have large groups of language learners in their classrooms can often resist “taking time away” from their curriculum to add language instruction. The primary way I have found to address both of these gaps is through a disciplinary literacy approach. What is Disciplinary Literacy? Disciplinary literacy was developed by Shanahan and Shanahan (2008) to describe the literacy practices used within a specific academic or professional discipline. It differs from content-area literacy in its focus on literacy within a specific discipline, instead of general strategies that can be applied across all content areas. Students can benefit from a strong base of content-area literacy to learn how to approach academic texts; however, that only takes them so far. Disciplinary literacy shifts the focus from being primarily a recipient of knowledge to becoming an active participant in the discipline, learning the ways of constructing knowledge and communicating that knowledge to others (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). Some key questions within a disciplinary literacy framework are:

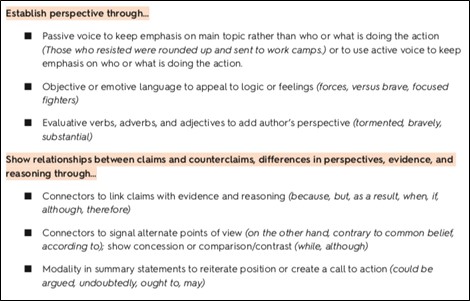

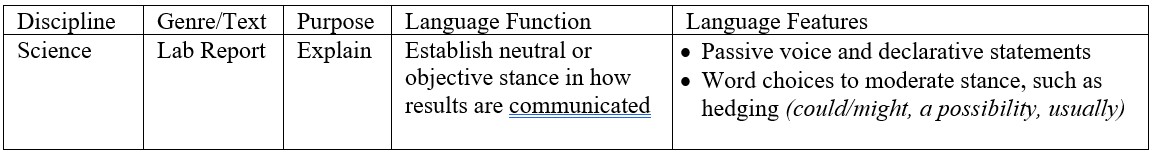

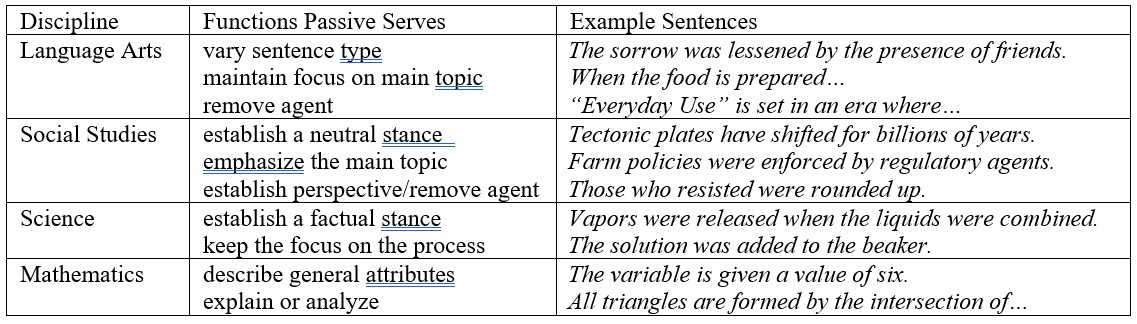

Mary Schleppegrell (2004) addresses the language of schooling from a functional linguistics perspective. Integrated with disciplinary literacy, it shifts the focus of academic language development from the general strategies often needed at beginning levels, to a deeper engagement of the ways of being and knowing through language. Language is no longer the sole goal, but a means to reach the goal of disciplinary participation. When learning and analyzing language at the word/phrase, syntax, and discourse level, the question consistently remains: How does this linguistic choice further the goal of this language function? What is the purpose this text, and therefore the language used within it, aims to fulfill? The WIDA Standards (2020), while focusing on K-12, provide a strong foundation for examining disciplinary literacy that can be expanded into post-secondary. The standards illuminate four Key Uses (narrate, inform, explain, and argue) across the four main content areas (language arts, social studies, science, and mathematics). The visuals below provide an example of the similarities and differences of language use within the disciplines. For example, each discipline interprets and constructs arguments, requiring the use of evidence, claims, and stances. However, how those are achieved differs. Figure 1 presents the language functions required to construct a strong argument within each discipline.  Figure 1. Language Functions within the Key Use of Argue – Expressive Figure 1. Language Functions within the Key Use of Argue – ExpressiveIn order to achieve these various language functions, students must learn how to use specific language features. These features, such as clause types, verb tenses, and specific types of nouns or qualifiers, are found across all disciplines but are used in different ways for specific purposes that are often invisible or unclear to novices. Figure 2 lists several sample language features needed to achieve Language Functions within the Key Use of Argue in Social Studies.  Figure 2. Social Studies Language Features (WIDA, 2020, p. 210) Examining Layers of Academic Language within Disciplines As the above images of the WIDA standards indicate, the academic language embedded within disciplines aligns with the purposes and functions of the discipline. When learning to identify academic language features, it is important to maintain the embeddedness with the discipline. With my pre-service teachers, we follow this pathway when discovering important linguistic structures: discipline – purpose – language function – language features. We also explore what genre best supports the purpose and language function. In cases where a specific genre is required by the curriculum, we begin with it and then analyze the purpose, function(s), and feature(s).  Table 1. Levels of Language Analysis Language function and features from WIDA ELD Standards (2020, p. 194) In all of these instances, the WIDA Standards (2020) provide a way for content-area teachers to see the academic language of their discipline. Teachers have often become so accustomed to its use that it has become invisible to them (Westerlund & Besser, 2021). Once they are able to see the language functions and features, they are then able to construct mini-lessons to address its use. From the lab report example above, science teachers developed materials to support students’ use of passive voice and provided a list of phrases, with accompanying example sentences, that demonstrated how to moderate or qualify findings. These simple tools made the necessary language more visible and attainable for all students. Exploring Language Features Across Disciplines While the exploration of language by discipline described above works in content-area classrooms, English language teachers rarely have the opportunity to explore disciplinary genres in such depth. In the language-focused classroom, the exploration can be reversed. For example, if teaching the construction of passive voice, purposes and examples pulled from disciplines can make the teaching more varied and applicable. The WIDA ELD Standards can then help make disciplinary usage visible to the language teacher.  Table 2. Uses of passive within disciplines Functions and sentences from throughout WIDA ELD Standards (2020) Table 2. Uses of passive within disciplines Functions and sentences from throughout WIDA ELD Standards (2020)When transitioning to academic writing, too often students are told one thing about passive voice—don’t use it. However, as the table above shows, there are many contexts in which students will encounter passive voice and many reasons that require them to produce it! When teachers have this knowledge and teach it, students then have the ability to identify the structure, critique its use (Is it being used to hide the agent in historical contexts and therefore minimize the role of the agent?), and produce it as needed. In this case, the language teacher’s use of disciplinary examples prepares students with a more complex view of language features which will prepare them to be more successful in content-area courses. Resources In this article, I have used the WIDA ELD Standards because they combine the four main content areas in one document that is free to access. There are many more resources available, especially when exploring specific disciplines. Key Researchers:

References Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective. Routledge. Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 40-59. Westerlund, R., & Besser, S. (2021). Making language visible in content area classrooms using the WIDA English Language Development Standards Framework. MinneTESOL Journal, 37(1), 9. WIDA. (2020). WIDA English language development standards framework, 2020 edition: Kindergarten–grade 12. Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Dr. Sara Vroom Fick teaches courses in education, specifically ESL and bilingual education, for pre-service teachers at Wheaton College. Her passion for disciplinary literacy and content-area teacher development stem from years of teaching in content-based ESL programs and collaborating with general education teachers. She counts it as a distinct privilege to prepare the next generation of specialists and general educators to support multilingual students. She can be reached via email at sara.vroomfick@wheaton.edu. | |

| Fall 2023 - Volume 51, Number 2 |