|

| |

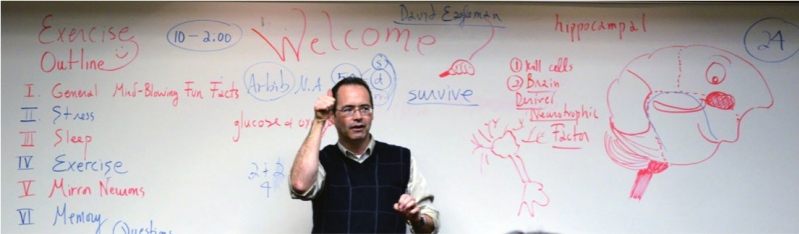

Implementing the R.E.S.T. Method to Break the Ebbinghaus CursePatrick T. Randolph, Western Michigan University  This article is the fifth in a multi-article series based on “What Every Teacher Needs to Know About the Brain,” a presentation given at the 2013 ITBE Convention in Lisle, IL. Introduction One of the oldest and most daunting facts for every language teacher who enters the classroom is this: Our students forget as much as 90% of what they learn within a mere 30 days. What makes matters worse is that most of the taught material is forgotten only hours after first “learning” it (Ebbinghaus, 1885/1913). For those of us who teach vocabulary, this is a rather grim reality. And although this discovery dates back to 1885, current researchers in neuroscience reconfirm Ebbinghaus’s troubling discovery (Kandel & Hawkins, 1992; Sousa, 2011). So, if what we teach is forgotten so quickly, can we ever really break this “Ebbinghaus Curse?” How do we get our students to remember the lexical items hours, months, or years after we have taught them? The answer to this is both inspiring and positive if we follow what I call the R.E.S.T. Method.

R.E.S.T., which is an acronym for Repetition, Emotions, Sensory Integration, and Teaching, is a part of a vocabulary teaching method I’m developing called the Head-to-Toe-Method. The essence of Head-to-Toe is to establish as many neural connections as possible related to lexical items. R.E.S.T. helps achieve this goal. In order to provide a workable application of this method, let me introduce each portion in as much detail as my limited space will allow. (R) Repetition and Spaced-Out Intervals of Review Repetition and spaced-out intervals of review are two powerful activities that are certain to break the Ebbinghaus Curse. Ebbinghaus himself (1885/1913) offered these as pivotal factors that substantially help learners retain newly learned material. What is the best way, then, to use these two crucial factors in class? First off, I would advise teachers to implement them from the start of each lesson. Let’s say, for example, one is teaching five new lexical items. First, I recommend instructors to elicit the definitions of the terms through a series of teacher-generated example sentences. This first step allows the students to hear and see the new terms a number of times in the initial minutes of the class. Once the definitions and registers are addressed, have the students supply example sentences. These initial steps provide both repetition and spaced-out intervals of review in the first half of the class. Next, as the lesson moves on, the instructor should designate the upper left hand area of the board as the “vocabulary corner” and write out the terms again. He or she can refer to them during the course of the class. This will allow for continual repetition and re-exposure to the terms up to the closing minutes. In order to reinforce the learning accomplished in class, students should review the terms and try to incorporate them in their “life after their ELL lessons.” They can do this by using them in conversations, conducting interviews using the terms, or by simply doing self-quizzes. (E) Emotions and Personalizing the Vocabulary Neuroscientists tell us that if we want our students to learn, we need to incorporate more emotions in the lessons. Emotions are the all-encompassing motivators for learning: They make us mentally alert, help elicit important neurotransmitters that strengthen learning outcomes (Jensen, 2008), and they inspire us to reach our language learning goals. What, then, are the best ways to use the emotions in an attempt to break the Ebbinghaus Curse and help our students retain the vocabulary we teach? A key factor is to have your students create example sentences of the vocabulary items in class. This is important for a number of reasons: first, it reinforces the previous idea of repetition and spaced-out intervals of review; second, it fosters an immediate personal bond between the students and the terms; and third, it creates a sure sense of “word ownership” in the students’ psyches (Randolph, 2013). Another equally effective use of emotion is a point from my Head-to-Toe Method, which requires the students to associate an emotion with the term being studied. For example, when I ask the students what emotion they associate with the three-part phrasal verb, “come up with,” they often respond with, “happy,” “joy,” or “surprise.” When I ask why they choose these emotions, they answer, “Because coming up with or creating something new is a happy, surprising or exciting experience.” (S) Sensory Integration: Multisensory Learning All learning embraces the senses, especially the acquisition of vocabulary in our native language. For instance, when we learned the word “grape” as a child, we first saw the color (green or purple). Next, we may have held one in our fingers and felt its texture. Then, we bit into it and tasted its sweet flavor and smelled its cool freshness. As we bit into it, we may have heard the crisp, crunch of the grape. All of these sensory qualities helped play a part in the acquisition of the word. The above experience is what I urge us to mimic in the classroom by using “imagined-sensory-associations” with words and phrases. For example, I recently taught the tri-part phrasal verb “look up to.” After going over the definition and register, I asked the students what color they associated with this phrasal verb. One student said “light green.” When I asked her why “light green,” she said that she really “looked up to” her high school math teacher, and that teacher often wore light green blouses and slacks. She went on to say that she smelled “apples” because that same teacher always ate an apple after class. By engaging the senses for vocabulary lessons, we are essentially creating and building a whole new network of neural connections to help the students transfer the lexical items into their long-term memory (Willis, 2006). For the more associations we develop, the more faculties the students can utilize. In using the senses as a tool for teaching vocabulary, we are really using a very natural and genuine approach to learning by incorporating the learner’s background with the meaning and association of the lexical item. (T) Teaching Others and Talking About What You Learn In 1972, Craik and Lockhart came up with the idea of elaborative rehearsal. This means we can retain information if we process it in an “elaborate” way via making associations, thinking, and or talking about the information in question. The final part of my R.E.S.T. Method, then, deals with reinforcing the learning of the newly acquired material by teaching it to others and using discussion to fuse old and new associations with the lexical items. In doing so, students will naturally practice each element of the R.E.S.T. Method: (1) they will repeat the lexical items; (2) they will add emotion and personalize the examples; (3) they will integrate a sensory aspect; and (4) they will talk about the terms in a reflective and analytical way. After the students have learned their vocabulary terms for the week, I pair them up for a “pair-quiz-review-session.” Here, through questions and answers, they go over the parts of speech, definitions, examples, colors, and emotions of the lexical items. During this activity, it is important that the instructor closely monitor the responses for definitions and examples, and correct any serious misuse of grammar. Concluding Remarks At first blush, Ebbinghaus’s discovery may cause the English language instructor to balk at even stepping inside the classroom. On the other hand, such a discovery can also energize the optimist in any educator and inspire him or her to rise to the challenge and break the age-old curse. The R.E.S.T. Method is my own personal response to Ebbinghaus’s discovery. And by using this method, I have managed to help my students learn and remember the lexical items I teach long after they have moved on from my ELL classes. References Craik, F. I. M., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour, 11, 671-684. Ebbinghaus, H. (1885 / 1913). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology, translated by Henry A. Ruger & Clara E. Bussenius. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University. Jensen, E. (2008). Brain-based learning: The new paradigm of teaching. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Kandel, E., & Hawkins, R. (1992, September). The biological basis of learning and individuality. Scientific American, 79-86. Randolph, P. T. (2013). What’s in a name? Personalizing vocabulary for ESL learners. CATESOL News, 44, 12-13. Sousa, D. A. (2011). How the brain learns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, A Sage Company. Willis, J. (2006). Research-based strategies to ignite student learning: Insights from a neurologist and classroom teacher. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Patrick T. Randolph currently teaches at Western Michigan University where he specializes in creative and academic writing, speech, and debate. ITBE member, Patrick T. Randolph, gave three presentations at this year's TESOL Convention in Portland, Oregon. He co-presented "Cat Got Your Tougue? Classroom Practices for Teaching Idioms" with Paul McPherron; solo presented "Using Adverbials to Generate Song Lyrics and One Act Plays;" and co-presented "Speaking Projects That Work: From Simple Narratives to Cultural Examinations" with Nicholas Margelis. Randolph’s article, “Tell Me About the Personality of Your Word—Developing Critical Thinking Through Creative Writing” was published in CATESOL News, V45, N4; and his article “Exploring Creative Writing and Critical Thinking With ELLs” was selected by TESOL Connections for their March issue. *Photo Credit: Kelly Cunningham | |

| ITBE Link - Volume 41 Number 4 |